mariaevinne

New member

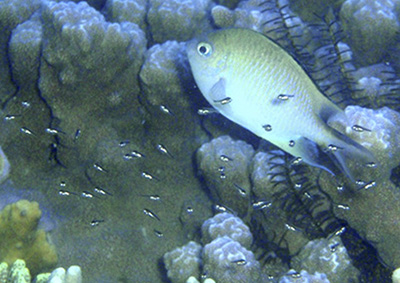

Among the hundreds of species of damselfish, only a few protect and care for their young; a newly discovered species raises the number from three to four.

The vast majority of coral reef fish produce large numbers of young that disperse into the ocean as larvae, drifting with the currents before settling down on a reef. Giacomo Bernardi, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz, studies reef fish that buck this trend and keep their broods on the reef, protecting the young until they are big enough to fend for themselves.

On a recent trip to the Philippines, Bernardi and his graduate students discovered a new species of damselfish that exhibits this unusual parental care behavior. Out of about 380 species of damselfish, only three brood-guarding species were known prior to this discovery. Bernardi's team had gone to the Philippines to study two of them, both in the genus Altrichthys, that live in shallow water off the small island of Busuanga. On the last day of the trip, the researchers went snorkeling in a remote area on the other side of the island from their study site.

"Immediately, as soon as we went in the water, we saw that this was a different species," Bernardi said. "It's very unusual to see a coral reef fish guarding its babies, so it's really cool when you see it."

Genetic tests on the specimens they collected confirmed that it is a new species, which the researchers named Altrichthys alelia (Alelia's damselfish, derived from the names of Bernardi's children, Alessio and Amalia, who helped with his field research). A paper on the new species was published May 18 in the journal ZooKeys.

Parental care dramatically improves the chances of survival for the offspring. According to Bernardi, less than one percent of larvae that disperse into the ocean survive to settle back on a reef, whereas survival rates can be as high as 35 percent for the offspring of the Altrichthys species. Yet the parental care strategy remains rare among reef fish.

"It's a huge fitness advantage, so why don't they all do that? There must also be a huge disadvantage," Bernardi said.

One big disadvantage is that the young are unable to colonize new sites far from the home reef of their parents. As a result, brood-guarding species (the technical term is "apelagic" species, because they don't have a pelagic, ocean-going phase) tend to occur in highly restricted areas, which leaves them more vulnerable to extinction.

"I suspect that species evolve this strategy regularly, and they are successful until there is some change to the local habitat, and then the whole population gets wiped out," Bernardi said. "These are very fragile species. The Banggai cardinalfish is one that was discovered just a few years ago in a small area in Indonesia, and it's already on the endangered species list."

Bernardi's graduate students, Gary Longo and Angela Quiros, are coauthors of the paper. This research was funded by the National Geographic Society and the UCSC Committee on Research.

The vast majority of coral reef fish produce large numbers of young that disperse into the ocean as larvae, drifting with the currents before settling down on a reef. Giacomo Bernardi, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz, studies reef fish that buck this trend and keep their broods on the reef, protecting the young until they are big enough to fend for themselves.

On a recent trip to the Philippines, Bernardi and his graduate students discovered a new species of damselfish that exhibits this unusual parental care behavior. Out of about 380 species of damselfish, only three brood-guarding species were known prior to this discovery. Bernardi's team had gone to the Philippines to study two of them, both in the genus Altrichthys, that live in shallow water off the small island of Busuanga. On the last day of the trip, the researchers went snorkeling in a remote area on the other side of the island from their study site.

"Immediately, as soon as we went in the water, we saw that this was a different species," Bernardi said. "It's very unusual to see a coral reef fish guarding its babies, so it's really cool when you see it."

Genetic tests on the specimens they collected confirmed that it is a new species, which the researchers named Altrichthys alelia (Alelia's damselfish, derived from the names of Bernardi's children, Alessio and Amalia, who helped with his field research). A paper on the new species was published May 18 in the journal ZooKeys.

Parental care dramatically improves the chances of survival for the offspring. According to Bernardi, less than one percent of larvae that disperse into the ocean survive to settle back on a reef, whereas survival rates can be as high as 35 percent for the offspring of the Altrichthys species. Yet the parental care strategy remains rare among reef fish.

"It's a huge fitness advantage, so why don't they all do that? There must also be a huge disadvantage," Bernardi said.

One big disadvantage is that the young are unable to colonize new sites far from the home reef of their parents. As a result, brood-guarding species (the technical term is "apelagic" species, because they don't have a pelagic, ocean-going phase) tend to occur in highly restricted areas, which leaves them more vulnerable to extinction.

"I suspect that species evolve this strategy regularly, and they are successful until there is some change to the local habitat, and then the whole population gets wiped out," Bernardi said. "These are very fragile species. The Banggai cardinalfish is one that was discovered just a few years ago in a small area in Indonesia, and it's already on the endangered species list."

Bernardi's graduate students, Gary Longo and Angela Quiros, are coauthors of the paper. This research was funded by the National Geographic Society and the UCSC Committee on Research.